Get ready for the shock of the new , or, in this case, the old. This disc of Beethoven concertos by keyboardist Arthur Schoonderwoerd has a highly unusual sound, even by the standards of the historical-performance movement. Performances of the Beethoven concertos in period style are rarer than those of the sonatas, which are themselves rarer than those of music by Mozart and Haydn. This is partly because the whole issue is more problematical with Beethoven, who was clearly striving toward larger dimensions. But Schoonderwoerd makes some educated guesses about actual pianos, ensembles, and techniques that might have been used, and apparently were used at times. The most bizarre effects come not from the fortepianos, a pair of Viennese instruments of types that have been heard  on other recordings, but from the small ensemble, with just five stringed instruments, and from Schoonderwoerd's practice of using the piano to double the rhythms in some of the full-orchestra passages. It is doubtless possible to find documentary evidence for each of these innovations, although too many pianists confuse evidence that something did at times happen with evidence that the composer wanted it to happen that way. How does it work musically? The small orchestra may be debatable as an "authentic" practice (performances of some of Haydn's late works are said to have involved hundreds of musicians), but the spotlight that it puts on the pianist during much of the otherwise neutral passagework is startling and often reveals ways in which such passagework is part of the contrapuntal web. The most interesting effects come in the slow movement of the piano arrangement of the Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61, here atypically designated the Piano Concerto No. 6; a little misleading, although the arrangement is Beethoven's own. The movement is taken at a brisk clip, and the new textures of the piano part are brilliantly shown by Schoonderwoerd's chamber-sized ensemble. The winds and brasses, all period instruments from the ranks of the specialist ensemble Cristofori, are also beautifully detailed here. Having the piano accompany the tutti as a way of adding rhythmic oomph will work less well for many listeners. One might remark that having the piano as part of the orchestra had been sufficiently old-fashioned for Haydn several years earlier that he treated it as a sort of joke in the Symphony No. 98, and in a structure like that of the opening movement of Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor, Op. 37, it cannot help but detract from the impact of the piano's entrance, carefully set up in what was a unique way for the time. Experimenters and speculators will love this disc, which is gorgeously illustrated with a fully analyzed portrait by Ingres. It's assuredly not for everyone, however. ~ James Manheim, Rovi

on other recordings, but from the small ensemble, with just five stringed instruments, and from Schoonderwoerd's practice of using the piano to double the rhythms in some of the full-orchestra passages. It is doubtless possible to find documentary evidence for each of these innovations, although too many pianists confuse evidence that something did at times happen with evidence that the composer wanted it to happen that way. How does it work musically? The small orchestra may be debatable as an "authentic" practice (performances of some of Haydn's late works are said to have involved hundreds of musicians), but the spotlight that it puts on the pianist during much of the otherwise neutral passagework is startling and often reveals ways in which such passagework is part of the contrapuntal web. The most interesting effects come in the slow movement of the piano arrangement of the Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61, here atypically designated the Piano Concerto No. 6; a little misleading, although the arrangement is Beethoven's own. The movement is taken at a brisk clip, and the new textures of the piano part are brilliantly shown by Schoonderwoerd's chamber-sized ensemble. The winds and brasses, all period instruments from the ranks of the specialist ensemble Cristofori, are also beautifully detailed here. Having the piano accompany the tutti as a way of adding rhythmic oomph will work less well for many listeners. One might remark that having the piano as part of the orchestra had been sufficiently old-fashioned for Haydn several years earlier that he treated it as a sort of joke in the Symphony No. 98, and in a structure like that of the opening movement of Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor, Op. 37, it cannot help but detract from the impact of the piano's entrance, carefully set up in what was a unique way for the time. Experimenters and speculators will love this disc, which is gorgeously illustrated with a fully analyzed portrait by Ingres. It's assuredly not for everyone, however. ~ James Manheim, Rovi

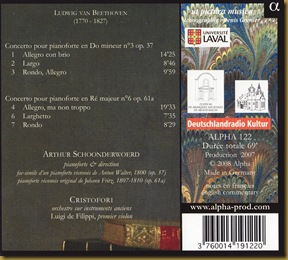

CD INFO

Ape, scans